CANYON DIABLO,

ITS DEVILISH HISTORY

by

Ann T. Strickland

1994

The history of Man in the area around

Canyon Diablo, Arizona dates back to the Dawn Men, the first aboriginal

inhabitants, followed by the Basket Makers, then Pueblo periods I and II, when

these people built dwellings in the cliffs of the canyon. The greatest density

of inhabitants was between 1050 and 1600, with the greatest Indian population

from 1050 to 1300, when the land on the Coconino Plateau was made fertile by

the disintegration of the volcanic fields from the San Francisco Mountains to

the west.

THE CRATER

Even before Man was known to live in

this area, some 22,000 years ago, a giant nickel-iron meteor weighing several

million tons and traveling at a speed of 133,000 miles per hour had plunged

into the earth, creating a huge crater just east of Canyon Diablo, and

destroying all life for a 100 mile radius. The meteor is estimated to have been

only 81 feet in diameter, though the crater today is nearly a mile in diameter

and is nearly 600 feet deep. Some prehistoric peoples left ruins within the rim

of the crater, indicating that they found it a suitable place to live.

The Meteor Crater wasn't considered to

have been caused by a meteorite until 1886, when sheepherders found pieces of

meteorites near Canyon Diablo. In 1891, a leading geologist, G. K. Gilbert,

declared that the crater had not been made by a meteor. It wasn't until 1903

when Dr. Daniel Barringer, a mining engineer who was convinced that a large

metallic meteor had created the crater, began drilling at the site but was

unsuccessful in mining the mineral.

His project to locate the main

mass of the meteorite was abandoned in 1929 after drilling to a depth of nearly

1400 feet on the southeastern slope of the crater. Modern technology reveals

that about 80% of the meteorite had been vaporized on impact and that only

about 10% still lies beneath the south rim. An excellent museum at the site tells the story very well.

The first known

Europeans to see Canyon Diablo were Spaniards from part of Coronado's

expedition into New Mexico in 1540-42. They were led by Captain Don Garcia de

Cardenas, and had been sent by Coronado from the Hopi villages to find the

Grand Canyon of the Colorado River. They crossed Canyon Diablo where it enters

the Little Colorado River.

TRAVELERS AND

TRADERS

For the next 300 years, countless

explorers, settlers, traders and treasure seekers, trying to establish a direct

route to the beautiful San Francisco Peaks on the western horizon and from

there to the Pacific, forced to

make a detour of some 25 miles either north or south in order to proceed across

the Little Colorado River. In 1853, Capt. Amiel W. Whipple, on his historic

thirty-fifth parallel railroad survey for then Secretary of War Jefferson

Davis, reached the edge of the deep gorge and dubbed it Canyon Diablo. He wrote

in his journal, "we were all surprised to find at our feet, in magnesium

limestone, a chasm probably one hundred feet in depth, the sides precipitous,

and about three hundred feet across at the top. A thread-like rill of water

could be seen below, but descent was impossible. For a railroad it could be bridged and the banks would

furnish plenty of stone for the purpose." It was almost three decades

later that Whipple's estimate of the depth of this canyon was found to be

lacking 155 feet.

Spaniards were passing continually from

New Mexico through this area from 1750 on. The first American traders who are known about arrived in

1825. They were beaver trappers,

who did their trapping along the Little Colorado which, until the late 1880s,

contained a heavy growth of cottonwoods and willows extending out into the mud

flats. After the American

occupation of the southwest, the regular route from the east in a direct line

to the San Francisco Peaks on the horizon led traders and other travelers right

to the level rim of the chasm known as Canyon Diablo. From the Indians the travelers would learn that access to

water and a crossing point could be reached a few miles downstream. True, it was a fairly steep, rough

route, but it was certainly more possible than the one they had first

encountered.

Along these walls hundreds of names

were cut into the rock. Of the earliest still existing one can be read in part:

S .Bac -............

de

Julio 1830

Another has only

the date, 1849, legible, but dates from 1860 to the middle 1880s are many.

In 1854, only one year after Whipple

had been through this country and made his survey, Felix Aubrey, a Santa Fe

trader, laid out the first wagon route eastward across northern Arizona,

traveling from San Jose, California with sixty men to Santa Fe. When he reached

the west rim of Canyon Diablo, he was baffled until Indians told him he could

detour downstream. He then proceeded north along the rim to the regular

crossing. While at Canyon Diablo,

he met a large number of Indians, who traded him $1500 in gold nuggets for some

old clothing and blankets, but wouldn't disclose the source of the gold. After

reaching Santa Fe, he was killed in August of 1854 in a personal encounter. His

route was known after that as the California Santa Fe Trail.

The next major survey of the 35th

parallel was the famous Beale Camel Experiment in 1857. Again, Secretary of War

Jefferson Davis was the official largely responsible for this seemingly bizarre

endeavor of using the camels to pack supplies and equipment from Fort Defiance,

Arizona to California's eastern frontier. Seventy-nine camels, imported from

the Middle East through Texas seaports, were led by Arab, Greek and Turkish

camel drivers and commanded by colorful Ned Beale, later to become well known

as the one who carried the news of the California gold strike to President

Millard Fillmore. Beale's

expedition reached Canyon Diablo. His guide had warned him that he could not

cross this chasm so far south of the Little Colorado, but he had to find out

for himself, going north to the old trail. At this time the trail was

designated as the Beale Road. Beale took his camels to his ranch at Fort Tejon,

California. The following year, he made another trip along the road he had laid

out. The Civil War ended what had

been a successful experiment with camels able to carry 700 pounds each and

survive on the desert vegetation.

Plans for a railroad to the west coast were put on hold until the 1880s,

and the camels were sold or escaped into the wild. Some of those camels were seen in the area as late as

1900. Beale's Camel Road remained

the basis for the 1920's National Old Trail Highway, which we know as Route 66,

or for the younger ones of us, U.S.40.

THE RANCHERS

Activity in the area was not at a

standstill, however. Indeed, from 1860 on, sheep and cattle ranchers had

located not many miles away, and grazed their animals along Canyon Diablo. The

first big sheep man of importance was John Clark, who brought 3000 head of

sheep from California to the area for summer and fall grazing in 1875. The

following year William Ashurst, father of one of the first U. S. Senators from

Arizona, Henry Fountain Ashurst, located south and used Canyon Diablo ranges

part of the time. The same year, the Daggs brothers brought more than 10,000

sheep from California into the area.

THE TRADERS

During the 1850s, Apaches often raided

north, and Navajo families would find refuge in the depths of Canyon Diablo. It

was there, in the Canyon, that the pack train traders, the forerunners of later

established trading posts, would find them. By that time they were trading

lead, bullet molds, powder, dye, buffalo robes, cotton blankets, flints, Green

River knives, cloth, glass beads and imitation silver jewelry. In trade they

received from the Indians horses, mules and plain striped handmade woolen

blankets known as wagon blankets. One trader well known to the Navajo for many

years after, was called "Billikona Sani " (Old American). He arrived

during the summer of 1852, and spoke Navajo, indicating that he had probably

lived previously among the Navajo tribesmen. The wonderful magic which he

performed was mixing the raw alcohol he carried at one gallon to three of

water, and adding cayenne pepper and chewing tobacco. This was what was known

as Arizona Frontier Whiskey.

When the Navajo tribal roundup of 1864

began, many Navajo families fled into Canyon Diablo and its many caves to avoid

being discovered by U.S. troops. Eight-thousand Navajo were eventually

imprisoned at Fort Sumner, New Mexico for four years. Their livestock and land

were taken by the cavalry. The Civil War halted settlement for some years, but

after that war, the cavalry returned to battle the Indians, the first at Canyon

Diablo being on April 18, 1867. Herman Wolf, a beaver trader for many years in

this area, was setting up a large stockade picket post on the river downstream

from the mouth of Canyon Diablo.

He and the U.S. Army were both engaged in fighting renegade Indians. But

when most of the Navajo were released from Fort Sumner and returned to their

homes in 1868, many of them traveled down the Little Colorado basin, perhaps

thinking that the mere presence of a white man at Wolf Post afforded them

protection. From there they moved south into their old hunting grounds along

both sides of Canyon Diablo.

THE BRIDGE

It was not until November, 1881, that

the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad construction, running from Ft. Smith,

Arkansas across the plains to Albuquerque, and then west toward Los Angeles,

reached the eastern edge of 255 foot deep Canyon Diablo. Timber parts of the

bridge to span the gorge were pre-assembled elsewhere, but someone misread the

plans; the bridge came up several feet short. This mistake plus other financial

difficulties meant that construction was delayed for seven months.

By this time,

the remarkable Edward Ayers, later to become a chief benefactor of the Field

Museum and the Newberry Library in Chicago, had assembled a sawmill and taken

it to the end of the track, transported it by ox-team across the Little

Colorado and to Flagstaff, and wasted no time in establishing the Ayers Lumber

Company, which provided the lumber for the railroad as it proceeded west.

THE TOWN

While waiting for the bridge to be

built, the shack town of Canyon Diablo grew into a wild place populated by some

2,000 untamed citizens. The

yellow-painted depot, the section crew's house, stock pens, a water tank,

freight docks and warehouses stood at the western end of the town on railroad

property. From there a mile-long

row of tin, tar paper and canvas buildings extended eastward along both sides

of the one rocky street. Hell

Street had fourteen saloons, ten gambling houses, four houses of prostitution

and two dance pavilions, a grocery and dry goods store and several eating

counters. Murder on the street was

common and there was a holdup almost every hour. Tales about the exploits of colorful characters at Canyon

Diablo, including Billy the Kid, Keno Harry, Clabberfoot Annie and B.S. Mary

were every bit as wild as those told about Tombstone or Virginia City. The sawmill men and Flagstaff merchants

provided a salary for a marshal, but finding someone to fill the job was not

easy. The first marshal lasted a mere five hours before he was killed; the

second, two long weeks; the third, three weeks before he was shot with

forty-five slugs; the fourth, six days.

There followed a period when the town

was without a marshal, until a stranger, an ex-preacher from Texas, rode into

town carrying two pistols, and being spotted by the hiring committee, was

offered the job. Being hungry, he accepted, and lasted a record thirty days,

killing a man a day and wounding so many that the railroad hospital in Winslow

refused to accept any more gunshot victims. Canyon Diablo's Boot Hill, located

south of the railroad tracks, had 35 graves at one time, but most bodies were

buried throughout the town, wherever they fell.

When Flagstaff businessmen appealed

to Territorial Governor Frederick Little for help, he requested that the army

restore order. However, by the time the army was to be deployed, the gorge of

Canyon Diablo was bridged, and the railroad proceeded on west to California.

This, which was claimed to be the highest railroad in the world, had cost

$200,000. Completed in June, 1882 after one year, it was 541 feet long, 223

feet high, 11 spans at 30-300 feet each, and used 1489 cubic yards of masonry.

When the first train rolled over it at 3:37 on July 1, 1882, the rip-roaring

town of Canyon Diablo died overnight. Whereas during the previous two years

Canyon Diablo had been the railhead for Flagstaff and Prescott, with large

loads of freight being transferred to wagons and proceeding north on the east

rim of the canyon to the old crossing, with passenger trains making regular

runs from Winslow and a regular stage line being operated from Flagstaff to

Canyon Diablo, the importance of the town as a transportation hub was

non-existent once the bridge was built.

The location became famous as a site

for train robberies, the most lucrative being in 1889 when a train had stopped

at the station to take on water, and was robbed by four men, who managed to

take the contents of the safe, as well as watches and jewelry. Sheriff Bucky

O'Neill and several other officers pursued the four cowboys into Utah and back

into Arizona, where they were captured. One escaped, the others were imprisoned

at Prescott, but of the over $100,000 in loot they had stolen, only $100 was

found on them, leading to the belief that they had buried the rest of it below

the rim of Canyon Diablo. The

treasure has never been found but many have searched for it ever since.

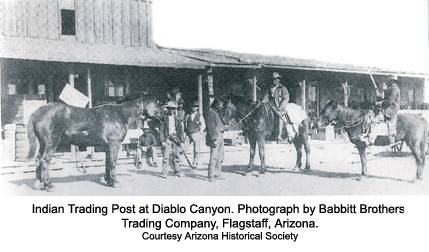

CANYON DIABLO

TRADING POST

The year 1886 was the year when Fred W.

Volz established a trading post at Canyon Diablo. The trading post was built

near the southwestern boundary of the Navajo reservation, and just a few yards

away from the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad depot at Canyon Diablo. Mr. Volz

was to remain there until 1910, establishing both a U.S. Post Office and a

Wells Fargo Station at the trading post. Since the Post was painted white, the

Navajo referred to it as Kinigai (White House). Their name for the Canyon was

Kinigai Boko (White House Canyon). Fred Volz and his wife were married during

these years and had one daughter, Jeanette, who lived there from 1890 to 1910.

MORE RECENTLY

To this day, both passenger and freight

trains speed along the Santa Fe Railroad (formerly Atlantic & Pacific)

tracks past the ruins of the trading post, and cross Canyon Diablo on the

bridge, rebuilt in the same spot as the 1882 bridge. The masonry bases of the

original bridge stanchions can be seen next to the bases of the present one.

The Canyon Diablo Train Station was a flag stop for many years after the town

died.

In 1934, Philip Hesch, signal

maintainer at Canyon Diablo Station married the widow of Earl M. Cundiff. The

Cundiffs had lived in the area for ten or more years, Mr. Cundiff had been shot

and killed in 1926 by a man who had leased the store they owned. 1934 was also

the year that the big trading post burned. That same year Mrs. Ray Thomas, with

an invalid husband, taught school at Canyon Diablo station.

Life goes on, at a slower pace, while

tourists speed by on U.S. 40. A sturdy barbed wire fence marks the line between

the southern boundary of the Navajo Reservation and the Atchison, Topeka and

Santa Fe railroad tracks. Just north of this fence, on Reservation land, the

rocky ruins of the Volz trading post seem not to have disintegrated markedly in

the last 30 years. A building dating back to the 1920s or 30s nearby has been

used as a souvenir store and as a fine modern ranch home, but was completely

vandalized some time in the last ten years. Where there was a road in 1963

leading from Route 66 to this spot, there is now only a trail requiring a four

wheel drive vehicle and a lot of determination to cover the one and a half

miles from U.S. 40 north along the Canyon toward the visible row of power poles

along the railroad. To mark the site of the once noisy town, there is only a

small, tired sign next to the tracks saying, very softly, "Canyon

Diablo".

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

1. "Arizona

Place Names", University of Arizona Press, 1988.

2. Cline, Platt:

"They Came to the Mountain". Flagstaff, Northland Publishing Company

with Northern Arizona University, 1976.

3. Kildare,

Maurice: "Dead Outlaw's Loot", True West, Jan.-Feb., 1967.

4. Richardson,

Cecil Calvin: "Canyon Diablo, the roughest, toughest hellhole of them

all", Arizona Highways, April, 1991.

5. Richardson,

Gladwell: "Two Guns, Arizona". no. 15 of a Series of Western

Americana, The Press of the Territorian. Santa Fe, The Blue Feather Press, 1968

.

6. Trimble,

Marshall: "Roadside History of Arizona",

Missoula,

Mountain Press Publishing Co., 1986.

With special

thanks to Buzz Strickland, Tim Strickland, Sally Berg and Tad Strickland for

their help, support and interest in searching and researching the history of

Canyon Diablo, which has fascinated me for most of my life.

Ann

T. Strickland Rowland

2005